The humble laws of basic arithmetic include the well-known concept of compounding. For Australian tax resident investors, there’s a more complex (and powerful) variant which is at play when they purchase a dividend paying share on the ASX and opt to participate in the dividend reinvestment plan (“DRIP”) of that company. I refer to this variant as “super compounding” and to understand it, we need to break down the 6 income components of a reinvested dividend. NOTE: only the first 2 are subject to income tax:

- Cash component: this is the easiest one to understand and requires no explanation. If and when a company declares a dividend of $1, the shareholders will receive a $1 cash payment for each share they hold.

- Franking credit: this is harder to understand. Franking credits are both statutory income AND tax offsets at the same time. The law is in 207-20 of the 1997 Income Tax Act if you want to give it a read on Austlii. While the shareholder is required to “gross up”, they are also entitled to an equal offset below the tax payable line. What this means is that, where the recipient shareholders marginal rate of income tax is higher than 30% (say 47%), then, the shareholder only pays the “top up tax” to their marginal rate – in this case, the excess 17%. Importantly, where the recipient shareholders marginal rate of income tax is lower than 30% (say 15%), then, the shareholder gets a cash refund for the 15% difference. This last one is particularly relevant to self-managed superfunds & gives rise to one form of tax arbitrage (risk free cash profit from a tax rate differential).

- “Look through earnings” / retained earnings: so, for example, the Australian big 4 banks only typically pay out in-between 70-80% of their cash profits generated. This is called their “payout ratio”. The remaining 25 cents is reinvested internally to increase moat and hopefully leads to higher real dividends in the future.

- Brokerage free allotment: when you participate in a DRIP, generally, there is no brokerage fee for you to be allotted the additional shares under the terms of the plan. This is a bigger benefit than it sounds like because just like returns compound over time, so do costs. And this benefit gets bigger as a shareholders position in the investee company grows. This is because brokerage fees are typically on a sliding scale hence the more shares you hold, the bigger your zero brokerage benefit becomes over time.

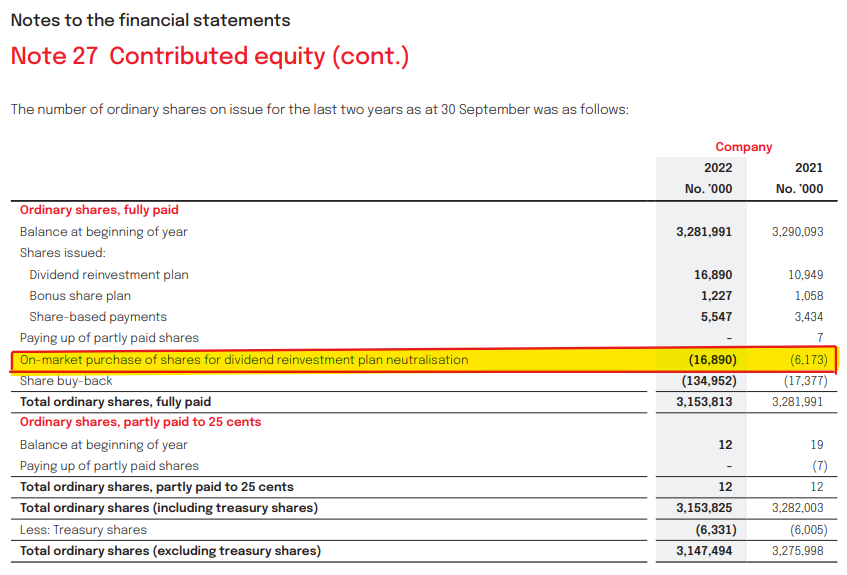

- Treasury concentration: often (but not always) treasury department staff inside your investee company will be actively managing the share register by, for example, ensuring that the company always holds enough shares in itself to satisfy any DRIP allocations which need to occur. Alternately, investees may buy shares on market to neutralize the effect of DRIP allocations. You can see this happening by reading the equity note in your investees annual reports – the NAB one is extracted below. This practice avoids share price erosion which occurs when investees simply issue more shares in themselves to satisfy DRIP allocations ie cutting the same pie into more (smaller) pieces. It also effectively makes each slice of the pie more valuable for the continuing shareholder over time.

- Gain on reinvestment price : the re-investment price (“RIP”) is usually set weeks before allotment. During the RIP window which typically lasts a week, the average price is set by averaging out the closing prices at the close of each trading day. By the time allotment rolls around, the RIP may be significantly less than market price per share. For example, the cash component of a dividend may be $5k, but the shares issued may have a market value of $6K on the allotment date. The unrealised increment in value is not subject to any form of income tax. It is important to note that this can also be a loss, however, for the long term holder, this loss will probably reverse over time, whereas any gain here is a tangible tax free benefit at allotment.

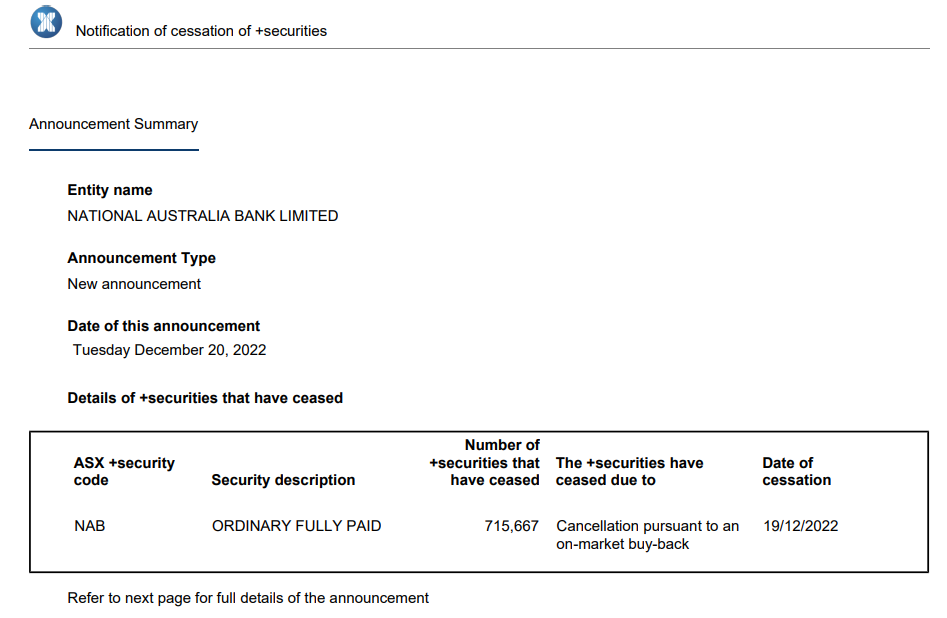

- Slice merging : Aside from treasury concentration, investee companies often will embark upon excess capital management by purchasing shares on market & simply cancelling those shares. Again, NAB did this with $5BN worth of excess capital (read “lazy cash”) in the 22FY. I have extracted one announcement below. This is done for many reasons, but the effect for the continuing shareholder and in particular for the dividend re-investor is to make each share in the company worth a smidgen more as you hold over time. As the number of slices into which the pie is cut decrease, the dividends paid on those shares will proportionately increase as will the share price.

So, there you have it. A summary of why and how dividend reinvestment works to deliver huge value to investors. Australian tax resident investors who do not get involved in this bonanza are acting illogically. This is particularly true in relation to our big banks which form a cartel and mutually reinforce each other’s profitability simply by existing as fail safes for one another. Far from accidental, this situation is in accordance with the Australian Federal Governments unofficial “4 pillars policy” which prevents the 4 from merging. Maybe its anticompetitive. However it has led to decades of stability and has also delivered the extraordinary result whereby our big 4 are among the largest and most stable banks in the whole world despite servicing a domestic population of only 30 million people (including NZ).

To discuss your situation and find out how dividend reinvesting can work for your family group, either inside or outside of super, contact Chris today at chris@solveaccounting.com.au